Restoring East Asia’s oldest stone pagoda

The 1,300-year-old pagoda in UNESCO-listed Mireuksa Temple site is the longest-running restoration project in Korea

By 이우영Published : Dec. 29, 2015 - 17:34

IKSAN, North Jeolla Province -- Restoring the seventh-century Baekje-era stone pagoda at the UNESCO-registered Mireuksa Temple site in Iksan, North Jeolla Province, has been a daunting task for archaeologists.

There were no proven historical records that could guide experts to recreate the original form of the ancient Buddhist pagoda.

“I went through every historical record from the 13th-century Samguk Yusa -- memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms. But no book had a record of how tall it was,” said Kim Derk-moon, director of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, who has been overseeing the restoration project for 15 years.

“A lot of things about the pagoda have been revealed during the restoration.”

There were no proven historical records that could guide experts to recreate the original form of the ancient Buddhist pagoda.

“I went through every historical record from the 13th-century Samguk Yusa -- memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms. But no book had a record of how tall it was,” said Kim Derk-moon, director of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, who has been overseeing the restoration project for 15 years.

“A lot of things about the pagoda have been revealed during the restoration.”

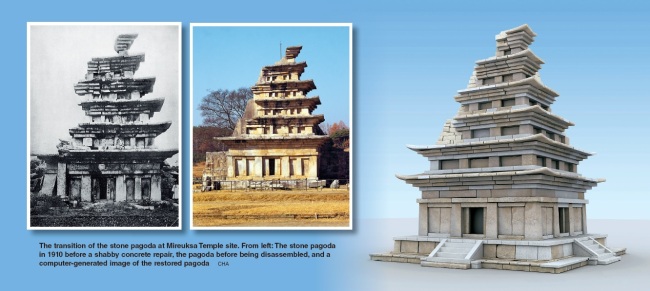

In 1999, the Korean government decided to restore the 1,300-year-old pagoda, which was showing severe signs of instability and decay. It took a decade to disassemble. Along the way, archaeologists found sariras and other artifacts, which revealed the pagoda’s original construction year.

Built in A.D. 639, the Mireuksa temple was a symbol of spiritual guidance and support for Baekje in its final years, amid growing threats from neighboring kingdoms. Baekje dissolved 21 years later, when it was defeated by an alliance between the Silla Kingdom and the Tang Dynasty of China.

Over the centuries, the pagoda observed the collapse of 700-year-old Baekje Kingdom and the rise of three new kingdoms afterward. It slowly deteriorated until it partially collapsed in the 18th century. A Joseon-era document depicted the pagoda standing seven stories tall, with piles of bricks supporting the pagoda to prevent its collapse. The pagoda decayed further to near collapse in the early 1900s. The destruction was shabbily prevented by covering the back of the pagoda with 185 tons of concrete during the Japanese colonial period.

Since then, it has stood six-stories tall on the western side of Mireuksa Temple site, one of the eight historical sites of the Baekje Kingdom added to UNESCO’s World Heritage list in July. The eight -- royal palaces, fortresses and tombs representing later periods of Baekje -- are scattered across the nearby cities of Gongju, Buyeo and Iksan.

While archaeologists and engineers were uncovering structural details of the pagoda, they discovered that it held high artistic and cultural value. Their findings show that the pagoda was the largest and oldest ancient Buddhist stone pagoda in East Asia and provides a window to an early Buddhist service and early styles of Buddhist pagodas.

Pagodas were important objects of worship for early Buddhists. The pagoda had an empty space on the first level so that people could walk in and perform religious rituals.

Its architecture is noted with a rare mix of features of wooden and stone pagodas, offering understanding in the transition of Buddhist pagodas in terms of materials and styles.

“What’s interesting about the pagoda is that it’s designed like wooden pagodas, but it’s built with stone,” said Kim.

Some mysteries of the pagoda’s structure have been solved.

The secret behind the durability of the stone pagoda, composed of thousands of pieces of sculpted stone, was the thin layers of soil between stone blocks. The layers acted like cushions, dividing the weight from top to bottom. Based on this ancient construction technique, modern scientists and engineers came up with a new method – mixing soil with minerals – to make the effect last longer.

The restoration team is using as many old stone pieces as possible and new stones only when necessary. Some old pieces are used in whole and some are cut and incorporated with new materials for enhanced durability. The restored pagoda will be 62 percent made up of old materials and is expected to finish in 2017.

To prevent the pagoda from looking too obviously restored, the art team is coloring new stone blocks. They put small dots of acrylic paint on the stones so as not to repeat the same mistake done on the restoration of the eastern pagoda of Mireuksa Temple. The eastern pagoda, recreated in 1993 after four years of construction, still looks like a replica. It is regarded as a “worst case restoration.”

Asked if the paint would wash off in the rain, Lee Dong-shik, preservation treatment researcher said that “the acrylic paint will bleach a few years later and the stone blocks will look natural, as if they were original.”

By Lee Woo-young (wylee@heraldcorp.com)

![[Hello India] Hyundai Motor vows to boost 'clean mobility' in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050672_0.jpg&u=)