Nuclear security diplomacy: A creative multilateral effort

By Korea HeraldPublished : March 26, 2012 - 20:07

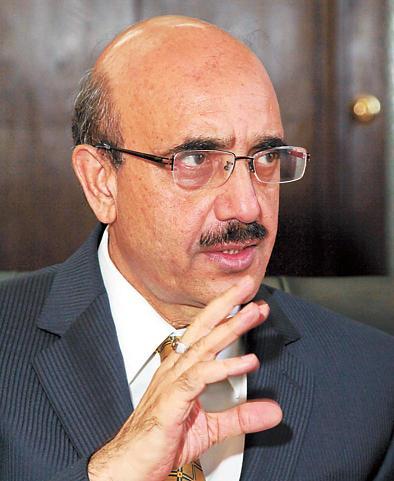

The following article was contributed by Masood Khan, Sherpa of Pakistan for the Nuclear Security Summit, on the occasion of the 2012 Seoul Nuclear Security Summit. ― Ed.

In April 2009, President Barack Obama announced that the United States would host a Global Summit on Nuclear Security within the next year. Since then, nuclear security diplomacy has assumed a distinct character and created a new deliberative process. The objective of this newly energized diplomacy is to enhance nuclear security and free the world from the fear of nuclear terrorist threats by taking concrete preventive steps.

Of course, work on nuclear security was in progress, but it needed strong political stimulus, which was given by the Washington Nuclear Security Summit in April 2010. The summit generated momentum for a shared vision of the leaders of 47 nations to secure nuclear materials and sites and erect barriers against nuclear terrorist threats. It also instilled a sense of urgency in the international community’s efforts in this regard.

The Republic of Korea’s President Lee Myung-bak took the decision to host the second summit to ensure that the new diplomatic tools to improve nuclear security were used effectively and the whole process was kept on track and taken to the next stage. The Republic of Korea has done a commendable job in steering the preparatory process and sustaining high-level attention to nuclear security. The fact that Seoul is hosting leaders of 53 countries and four multilateral bodies is a testament to its strong leadership on a pressing international issue.

In April 2009, President Barack Obama announced that the United States would host a Global Summit on Nuclear Security within the next year. Since then, nuclear security diplomacy has assumed a distinct character and created a new deliberative process. The objective of this newly energized diplomacy is to enhance nuclear security and free the world from the fear of nuclear terrorist threats by taking concrete preventive steps.

Of course, work on nuclear security was in progress, but it needed strong political stimulus, which was given by the Washington Nuclear Security Summit in April 2010. The summit generated momentum for a shared vision of the leaders of 47 nations to secure nuclear materials and sites and erect barriers against nuclear terrorist threats. It also instilled a sense of urgency in the international community’s efforts in this regard.

The Republic of Korea’s President Lee Myung-bak took the decision to host the second summit to ensure that the new diplomatic tools to improve nuclear security were used effectively and the whole process was kept on track and taken to the next stage. The Republic of Korea has done a commendable job in steering the preparatory process and sustaining high-level attention to nuclear security. The fact that Seoul is hosting leaders of 53 countries and four multilateral bodies is a testament to its strong leadership on a pressing international issue.

Pakistan has keenly participated in the Nuclear Security Summit. Prime Minister Syed Yusuf Raza Gilani, who heads our apex decision-making body National Command Authority, attended the first summit and will now be at the second summit in Seoul. In this respect, he represents continuity and Pakistan’s abiding commitment to nuclear security. Since the Washington Summit, we have established centers of excellence for training and emergency response mechanisms; upgraded physical protection arrangements; and revised export control lists. Following the Fukushima accident, we conducted thorough stress tests of our nuclear power plants. We are in the process of deploying special nuclear materials portals on key entry and exit points to deter, detect and prevent illicit trafficking of nuclear and radioactive materials.

What is so distinctive about the nuclear security diplomacy? One of its striking features is that the deliberations have been kept away from multilateral politics and a consensual, collegial approach has been adopted. The process has acted as a catalyst in creating sharp awareness about the need to upgrade physical protection at nuclear sites and secure nuclear fuels against theft and sabotage. It has also resulted in voluntary actions to reinforce nuclear security infrastructure. For instance, many countries have set up centers of excellence for nuclear security education, training and innovation.

The Washington Summit underlined the need to put in place minimum security standards for all nuclear reactors, plants, hospitals and research laboratories. While reaffirming its commitment to peaceful uses of nuclear energy and its growing need, nations have agreed to take steps to protect vulnerable materials. Many nations have reported that they are already doing that.

When Summit participants looked at the bigger picture, they realized that many initiatives have been taken discretely to tackle the issues of nuclear security, including nuclear terrorism; and that there was no synergy amongst various initiatives dealing with these subjects. The IAEA, the U.N. Security Council Resolution 1540 Committee, the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism, and the Global Partnership against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction, and a variety of treaty regimes have been working almost disparately, with minimum coordination and communication. The summit process has tried to create a shared space for discussion and coordination. It has also emphasized the central and integrating role the IAEA can play in nuclear security. Concrete measures have been suggested to further empower the IAEA.

A year-long preparatory process has distilled and identified 11 core themes of nuclear security: global nuclear security architecture; the role of the IAEA; nuclear materials; radioactive sources; nuclear security and safety; transportation security; combating illicit trafficking; nuclear forensics; nuclear security culture; information security; and international cooperation. By learning from each other in these areas and by moving in tandem, nations will take effective measures to enhance nuclear security. Nations through voluntary actions will work toward the success of the Summit decisions.

The most important agreement reached so far is to promote nuclear security culture and to anchor it in social values. It is not a narrow legal or bureaucratic option, but a much broader moral choice to save the world from natural and malicious nuclear disasters. The risks and responsibility are shared by societies at large.

Nuclear safety was not on the agenda of the Washington Summit, but after the Fukushima accident, it became imperative for Sherpas to address the safety aspects in one form or the other. The form they chose was the one dealing with the relationship between nuclear safety and nuclear security. Nations must take additional measures and maintain constant vigilance to prevent and respond to nuclear catastrophes, whether they are caused by accident or malicious acts. Such measures also guarantee that nuclear energy continues to enjoy support for safe, secure and peaceful uses.

The threat of radiological dispersal devices, or “dirty bombs” as they are colloquially called, was mentioned in passing in the Washington Communique but the Seoul Summit treats radiological security more appropriately. There is an emerging realization that the threat from the RDDs may well be more immediate and likely because evidence made public by IAEA’s Illicit Trafficking Database shows that it is much easier to possess, steal and traffic material for such devices and to assemble them. At the opening dinner of the Washington Summit, Gilani underlined that the threat of terrorist acts involving “dirty bombs” was more real and had a global dimension. But we believe that radiological security ought to be pursued in a manner that it does not affect genuine medical, industrial, agricultural and research uses of radioactive sources.

The negotiating process for the Washington and Seoul summits has been fair, transparent, and participatory. The credit for this goes to the able Korean and U.S. teams led by Kim Bong-hyun, deputy foreign minister, and Gary Samore, special assistant to the president and White House coordinator for arms control and WMD, respectively. The example for an inclusive and non-partisan format for discussions was set by the U.S. and was developed and refined by South Korea. In this atmosphere, the negotiators did not viscerally go for the lowest common denominator but worked to explore common ground and bridge differences for the best possible solutions.

It was also clear that the conveners of the Nuclear Security Summit had no intention of creating a new regime or a parallel international institution. The core objective was to give a strong political impetus to nuclear security through concerted action. The overall approach of the two-summit process has therefore been to encourage a peer review of the efforts being made at the national level and to internalize best practices in order to fortify safeguards around nuclear sites and stockpiles. The NSS process thus acts both as a backdrop and an enabler. In this context, it is important to factor in technical assistance for countries upon request.

The 2012 Nuclear Security Summit is to build on the unprecedented success and dynamism of the 2010 Nuclear Security Summit by adding fresh content and encouraging tangible steps to reduce the nuclear and radiological risks and to secure nuclear materials and sites. The efficacy of the NSS process will depend on broadening of its support and its inclusiveness. Pakistan will continue to work at the national level to maintain highest standards of nuclear security and work with the international community for greater synergy between different initiatives and institutions.

By Masood Khan

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Hello India] Hyundai Motor vows to boost 'clean mobility' in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050672_0.jpg&u=)