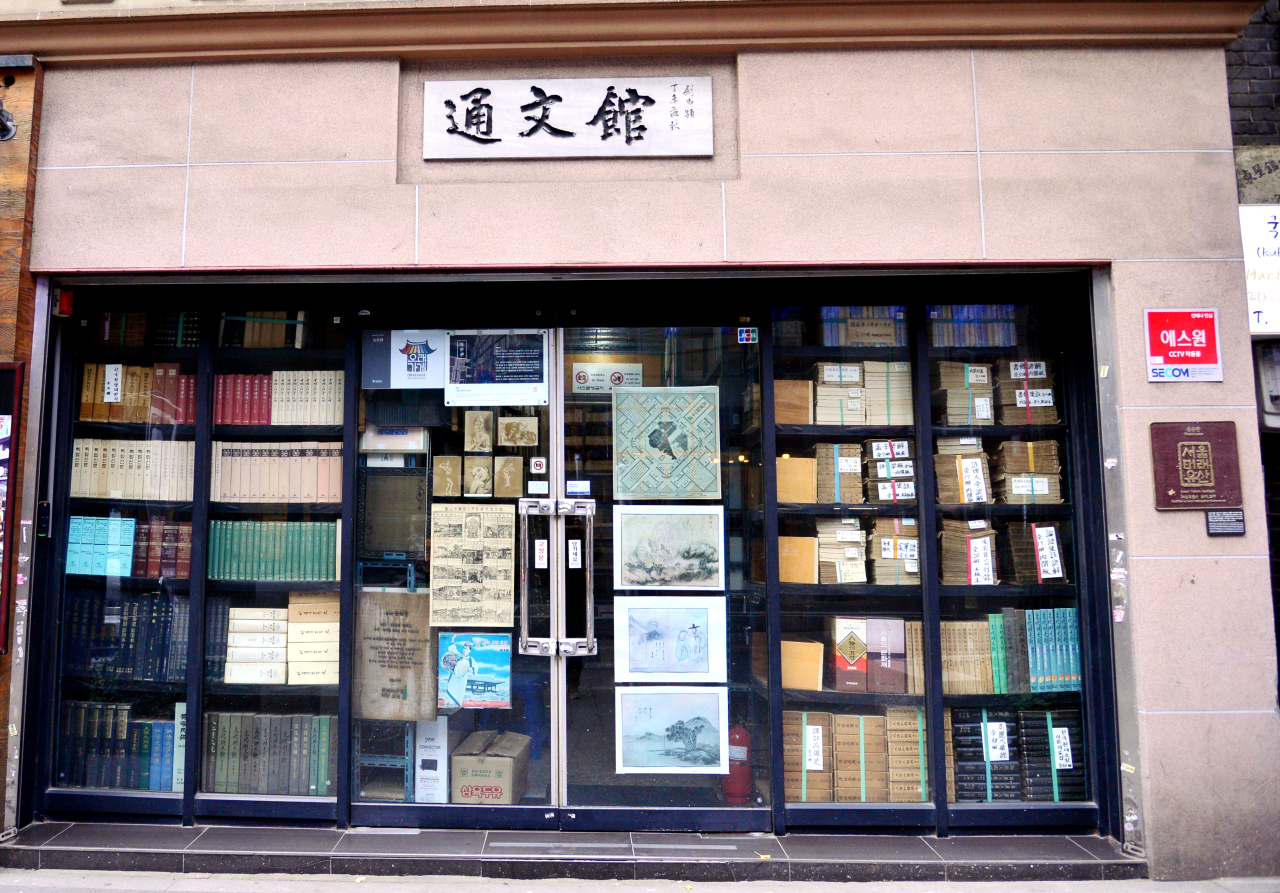

On the bustling main street of Insa-dong -- which once symbolized Korean traditional culture, but is now crowded with souvenir shops -- visitors nonchalantly pass by a store that holds centuries-old treasures.

Tongmunkwan, the oldest bookstore in South Korea, keeps its door closed most of the time.

Tongmunkwan, the oldest bookstore in South Korea, keeps its door closed most of the time.

Stepping inside, one is instantly overwhelmed by its massive collection of antique books, stacked from floor to ceiling, and the thick smell of old volumes. The oldest here is from the late Goryeo Kingdom (918-1392).

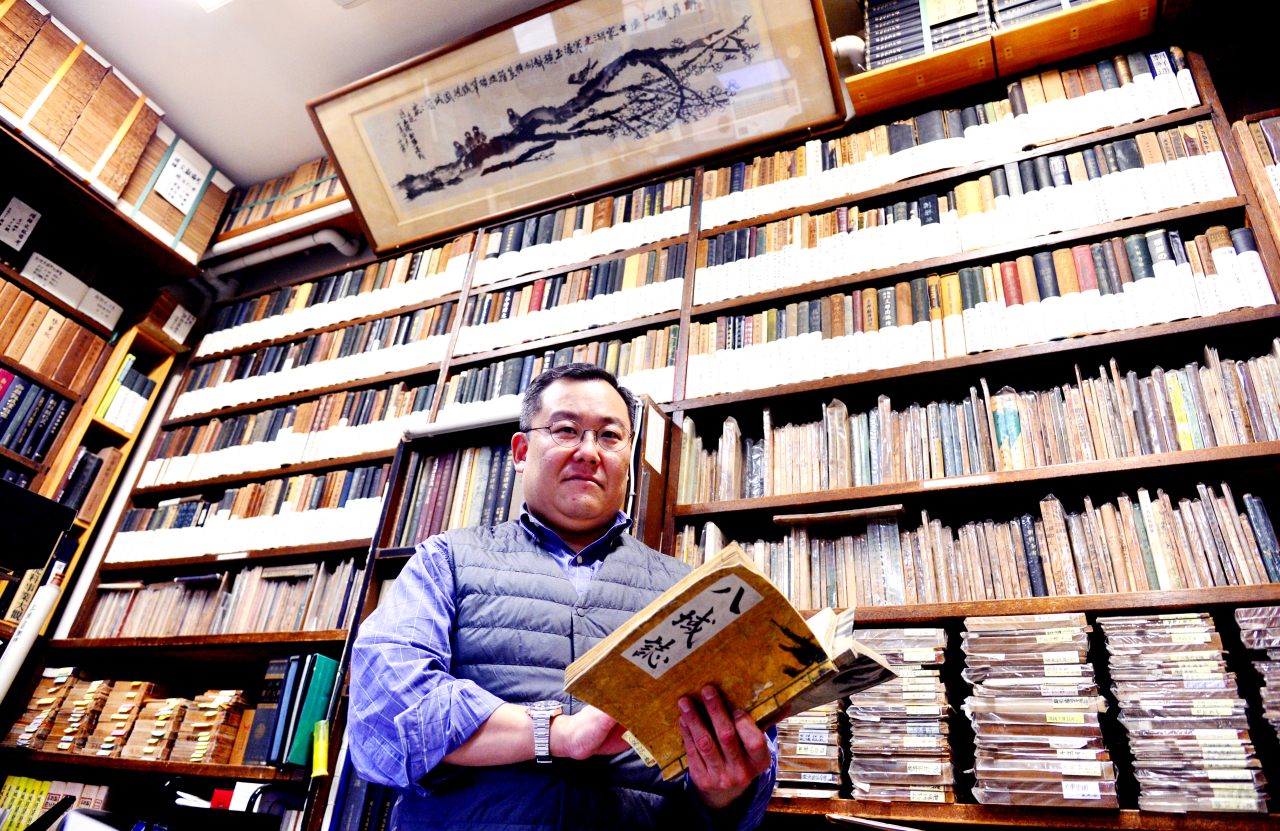

“Some people touch books carelessly,” said Lee Jong-woon, the third-generation owner of Tongmunkwan, when asked about the uninviting look of the shop.

“I want (only those) people who would treat books more carefully (to come in). Many of the books here are very old and fragile.”

In 1934, during the Japanese colonial era, Lee’s grandfather took over the bookstore from a Japanese owner. After Korea gained independence in 1945, he changed the name to Tongmunkwan, which means “a place where all books encounter.”

For more than eight decades, under the stewardship of Lee’s family, Tongmunkwan has grown to be a treasure trove of nearly 20,000 antique books -- some hundreds of years old. Within its collection are masterpieces of Korean literature.

Four years ago, the first edition of the poetry collection “Azaleas,” written in 1925 by the late Kim So-wol, was auctioned for 1.3 billion won ($1.1 million), a record for a Korean literary work.

“Such first editions are precious, and usually stored at home,” Lee, 49, said. “Unlike Western titles, old Korean books withstand humidity so they are relatively easy to preserve.”

Tongmunkwan’s customers include the National Museum of Korea and private museums, which purchase books of exceptional value. Prices are usually between 40 million and 50 million won.

Lee’s family has stuck to one rule: Do not bargain over a book’s price, and put a price tag on every book. This, according to Lee, builds trust with buyers.

“My grandfather used to tell me ‘don’t tell the price twice (don’t change the price), and don’t deceive buyers regardless of their age,’” he said, writing his grandfather’s words down in eight Chinese characters.

On his desk is a little note that reads “To the beginning.”

“You know it is very hard to lose the first resolution and control your mind,” the owner said. “I live by dealing with books, but once the money becomes a priority, it will ruin not only myself but this store,” Lee said.

He especially likes textbooks from the Korean Empire, which lasted only 13 years until Japan annexed Korea in 1910. That was a turbulent period when Western cultures were flowing in while some Confucian scholars strived to protect their culture.

“The textbooks issued by the government in the Korean Empire reflect exactly how confusing the period was,” Lee said. “It is interesting to see how books were made differently in two styles: a Western style and a traditional Korean style.”

While in a Western book, the lines are arranged horizontally and the pages are flipped from right to left, the opposite is true of Korea’s traditional books.

Searching for rare antique books is like seeking out hidden treasures -- like in the “Indiana Jones” movies, Lee said.

“I make trips to Japan and China regularly, usually five times a year, to seek out antique Korean books, which are neglected there as foreign books with no one realizing their value,” Lee said.

Lee said the business has not had a major crisis yet, despite the sluggish bookstore industry in general. “We are different from ordinary bookstores,” Lee said.

On the rapidly changing book scene with e-books, web publishing and so on, he just said, “Easy come, easy go.” He believes there’s something special about paper books.

“People can get easily distracted when reading digital books. But when you read a paper book, you have time to contemplate on the contents,” Lee said.

He is not sure how much longer Tongmunkwan will remain at its current location.

“I have a son who is a college student, but I am not sure if he wants to take over the store. He is young and the world is rapidly changing,” Lee said. “But I am teaching him some Chinese characters just in case.”

Looking at the main street of Insa-dong, he reminisced about the old days.

“Insa-dong has changed a lot … what I miss the most is kids playing on the street and seniors coming to play janggi (Korean style chess),” Lee said. “They are all gone now, except for this store.”

By Park Yuna (yunapark@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids to return soon: report](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050713_0.jpg&u=)