[Herald Interview] Life on street in North Korea

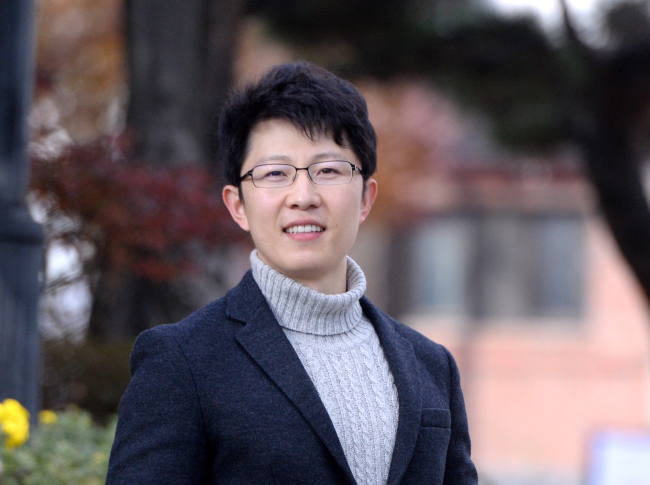

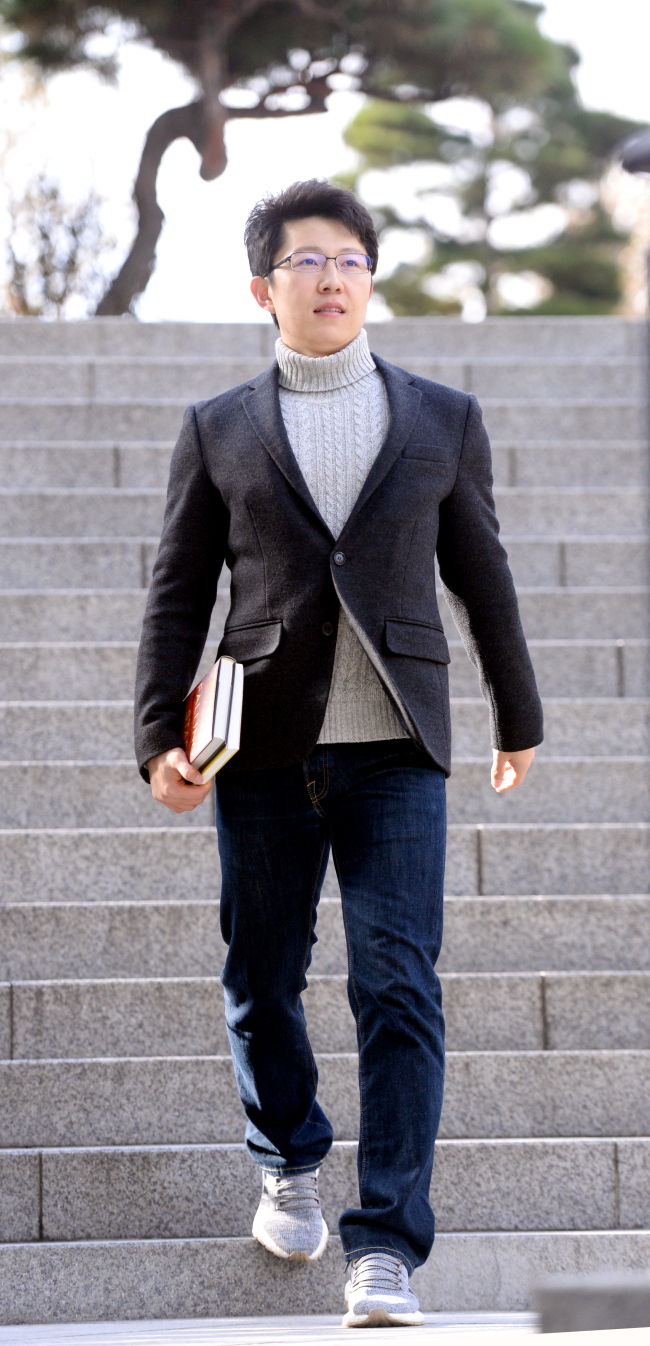

Defector-turned-activist Lee Sung-ju says millennials are key to change in the Stalinist regime

By Yeo Jun-sukPublished : Dec. 1, 2017 - 17:11

Born into a prestigious family in North Korea, Lee Sung-ju enjoyed an idyllic childhood of the selected few. Living in a three-bedroom apartment in Pyongyang, he attended Taekwondo classes, visited parks and took ferry rides.

But his comfortable life was shattered with the death of the North’s founding father Kim Il-sung in 1994. Lee’s father -- who had been working as an official of the guard unit for Kim Il-sung -- fell out of favor with the new regime led by Kim’s son, Kim Jong-il. And then, he was caught complaining “there is no future” in the Stalinist regime.

The cost for his slip of the tongue was much harsher than one can imagine. Lee’s family was forced to flee the prosperous capital and move to the northern city of Gyeongseong. Telling him to look for food, his parents left him and never returned. He was 12.

“When I was young, my dream was to become a military officer to protect our motherland from US bastards,” Lee, 30, said in an interview with The Korea Herald in Seoul. “But the dream was changed into having a solid three meals every day.”

Left with no choice but to fend for himself, Lee picked pockets and stole food from merchants. He banded together with six other boys to form a street gang which was more like a group of beggars. They are called “kkotjebi,” which means flowering swallows in Korean.

To avoid being caught, they would move from one town to another every few months. Almost every time, they clashed with other gangs who were already there.

It was often a life-and-death struggle, involving rocks and iron rods. In one such fight, a member of Lee’s gang received a blow to the head and died. Then his closest friend Young-bum was killed by a farm guard for trying to steal potatoes. He dug a grave and buried them by himself. Lee and Young-bum were 13.

“I had seven friends and Young-bum was the closest one. We were more like brothers. Before Young-bum died, he told me not to tell his parents he died. He asked me to tell them that he just left the gang. I cried my eyes out,” he said.

His life on the street went on for more than three years until he reunited with his grandfather. It turned out that his grandfather had never given up searching for Lee, coming to a train station every Sunday in the hopes of finding him.

One day, a mysterious man approached Lee with an important message. The stranger was a broker who helped North Koreans escape from the country. The man was sent by Lee’s father, who had defected to South Korea via China in 1998.

With the broker’s help, Lee crossed the Tumen River and came to China. With a fake passport, he boarded a plane to South Korea. A week after escaping the North, he was reunited with his father in November 2002 at the age of 16.

The last time Lee contacted his remaining family in North Korea was 2005. He then heard his grandparents were doing fine in Pyongyang, so were his aunts and uncles. His mother is still missing despite years of searching.

“Not all defectors’ family members face purges. It depends on how they treat it,” Lee said, responding to the question whether he is worried about the safety of his family in the North. “It’s OK. My father and I are documented as dead in North Korea.”

Finding a new hope in the South

His new life in South Korea was never easy.

He started going to middle school and made friends there, although he was three years older than his classmates.

But the most challenging part was to establish a new identity. Caught between his childhood memories in the North and his new life in the South, Lee had felt as if he was a stranger -- neither North Korean nor South Korean.

To pull himself together, he gave himself a mission: Rescue those facing the same fate as his in the North and bring them to the South safely. Now, the 30-year-old Lee works as an activist for Citizen’s Alliance for North Korea Human Rights.

“Later on, I realized that I am both North Korean and South Korean. So I am Korean. That was the new identity I found. It gives me the dream that I have to pursue: reunification of the two Koreas. That is the only way to bring me home.”

Lee has been focusing on young North Korean girls in China who suffer sexual assault and physical abuse after being married off to Chinese men for money.

Without no official status in China, those women have no idea what awaits them until they arrive. Having undergone horrendous abuses, some of them are sold off to another man again. In the worst case, their organs are removed for sale on the black market, he said.

Lee recalled a young woman who fled from her abusive husband with a 28-day-old baby. Despite the warning against the risk involving the escape, she said she would rather die with her baby than stay in China. When Lee met them in South Korea, the baby’s bellybutton was barely cut from umbilical cord.

“She was married to three different Chinese men beaten by the husband each time. Coming to South Korea via third countries from China is a very dangerous route. I told her it’s is so risky and the kid could die. She replied, ‘if the baby could die, it would have been dead already. We will leave anyway.’”

According to Lee, those defecting to South Korea come mostly from China. Most of them have lived there for about five years and experienced human rights abuses. Of the 70 women his organization rescued this year, 90 percent of them fell into this category, he said.

Bringing them to South Korea, too, is an arduous endeavor requiring an enormous amount of money and a complicated process. Crossing the Tumen River alone costs up to 20 million won ($18,000) to bribe North Korean border guards. The prices have risen lately due to the toughened border security, he said.

Regarding the reasons for fleeing from North Korea, most of them are still leaving the communist regime to survive, but indications emerge that an increasing number of North Koreans chose to defect for better education and an open society.

“There is a defector who left North Korea who wanted to become a judge after graduating from a prestigious law school in Seoul. He was denied such opportunity in the North because his aunt defected to South Korea. But I think it’s still a rare case. Most of them left for survival.”

Millennials are key to change in the North

For Lee, those defectors residing in South Korea can play a significant role in bringing forward the reunification of the two Koreas. The way they can contribute to the endeavor is through the money they send to their families in the North.

Although there is no official data on the remittance available due to the South Korean government’s ban on money wires to the North, the amount of remittance hovers around 30 billion won per year, Lee said.

According to statistics from the Ministry of Unification, a total of 30,490 North Koreans have resettled in the South as of March 2017. The annual average of remittance stood at 1.64 million won, according to a poll released by local daily Chosun Ilbo in January 2016.

Such an amount of money can help create “middle-class” merchants in North Korea, which is key to transforming the communist country into the market economy.

“Money sent to North Korea can become bidding money for commercial interactions,” said Lee. “Middle-class merchants felt they were blocked from such opportunities… they were caught between corrupt officials and big-shot merchants.”

When North Korea’s founding father Kim Il-sung and his son Kim Jong-il were in power, speaking out against the totalitarian regime was unthinkable. Those born in this era wouldn’t dare to topple their “dear leaders” -- an outcome of the decadeslong brainwashing program.

But the young North Koreans -- particularly those born in the 1980s and ‘90s who constitute roughly 25 percent of the population of nearly 25 million people -- are more individualistic than their parents. Instead of expecting the state to bail them out, they navigate for their own survival in a capitalist fashion, Lee said.

“Young North Koreans don’t have any fantasies about the era ruled by the Kim families. Of course, they also praise the regime and worship Kim Jong-un in public, but what they really focus on is how to make money.”

“Admittedly, those who rule North Korea right now are mostly born during the era when the North Korean economy is better than that of the South. So it’s almost impossible to see a collapse from within. But, 20 years from now, I think there will be a big change.”

By Yeo Jun-suk (jasonyeo@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)