By Ronald G. Knapp

(Tuttle Publishing)

Budding bridge engineers should look to Asia for inspiration.

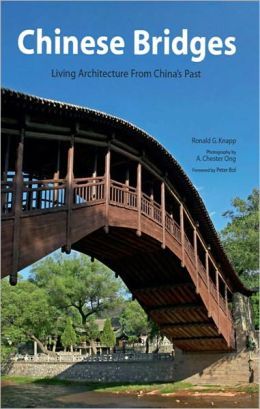

For thousands of years, China has built bridges for commerce, convenience and sometimes, to mark the “material achievements of emperors down through the ages,” says Ronald K. Knapp, writer of “China Bridges,” an oversized paperback coffee-table book.

“Born of necessity to span streams, valleys and gorges, bridges are literally underfoot and often inconspicuous,” says Knapp. Accompanied by photographer A. Chester Ong, he spent years researching and photographing all kinds of bridges, some of them spanning gorges in difficult terrain.

One of the most enjoyable parts of “China Bridges” is the juxtaposition of ancient Chinese art, scrolls and historical photographs with Ong’s beautiful photographs of bridges still in existence. A rubbing from the Eastern Han Dynasty (A.D. 25-220) shows chariots going across a bridge while on the opposing page, a scroll shows a similar structure from a painting from the 1600s. Readers will have a lesson in art and history as well as engineering.

The book has three parts. Part One is titled “China’s Ancient Bridge Building Traditions” and covers the many historical types, from “turtle bridges” defined as a “continuous but broken line of large stones” to “rainbow bridges” whose arches “using ‘woven’ timber as the underlying structure.” This type is best shown in a very famous 12th-century Song painting “Qingming Shan He Tu” by Zhang Zeduan.

The second part connects the bridges with Chinese folk culture. “A cursory examination of old bridges,” Knapp points out, “reveals that most are emblazoned with significant elements” with meanings that “surpasses mere ornamentation.”

Translation: they include mythical animals such as “writhing dragons playing with pearls,” stylized lions or pagodas to ward off malignant spirits. Some of them were Buddhist related. Many relate to “calming of water and protection against flood.”

The last part of the book goes in-depth about Chinese “heritage” bridges, such as the ones in Beijing’s Forbidden City and the famous Suzhou and Hangzhou garden bridges.

Here is where the book shines in introducing readers to history of the vast number and beauty of Chinese bridges all over the country, and they have been destroyed, and rebuilt over centuries.

Here, though, are examples of the fragility of some stone spans.

During the Taiping rebellion, (1850-1864), “an Englishman, Charles Gordon,” ordered a single arch of the Baodai bridge, near Wuxian, to “be removed to permit his vessel to pass.” The bridge, which was started during the 9th century Tang Dynasty and subsequently rebuilt several times, came crashing down, nearly sinking his boat, since the missing arch was instrumental in keeping rest in line.

In the forward, Peter Bol of Harvard University says, “Looking down to the riverbed, I see the marks of old foundations; the current bridge seems to be the third or fourth incarnation of a bridge at this spot.” There are multiple examples to be seen in “China Bridges.” (MCT)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Today’s K-pop] Ateez confirms US tour details](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050700_0.jpg&u=)