100 years after birth, Burroughs’ work still has power to shock

By Korea HeraldPublished : Feb. 13, 2014 - 19:24

Even sober, William S. Burroughs had visions.

As a young child, he saw a green reindeer the size of a cat. Another time, he woke to see tiny men scrambling among his building blocks, he said.

“He was one of those children who never really got over the magical kingdom. Part of him stayed there,” says biographer Barry Miles.

As a young child, he saw a green reindeer the size of a cat. Another time, he woke to see tiny men scrambling among his building blocks, he said.

“He was one of those children who never really got over the magical kingdom. Part of him stayed there,” says biographer Barry Miles.

Burroughs’ kingdom, literally speaking, began in a comfortable house in the Central West End of St. Louis, at 4664 Pershing Avenue (known as “Berlin Avenue” before World War I). Later, the family would flee the smoggy city for the suburb of Ladue.

Over his life, Burroughs traveled much of the world and found myriad substances to induce more visions and dreams, which he recorded in books or used as inspiration for art of one kind or another.

This week is the 100th anniversary of Burroughs’ birth ― on Feb. 5, 1914 ― and his literary kingdom is international, a destination for both scholars and modern beatniks. Novels such as “Naked Lunch,” “Junky” and “Queer” retain an outlaw reputation more than 50 years after he wrote them. The Burroughs oeuvre ― obscene, amoral, transgressive ― enthralls dedicated members.

“His work still has the power to shock, which is pretty hard these days,” Miles says.

Miles’ 700-page biography shows how Burroughs’ life was mirrored in his writing while warning that some of Burroughs’ tales were likely exaggerated.

One thing that wasn’t exaggerated was Burroughs’ addictions, even though he lived until 83.

“Considering what he did to his body over the years, it’s a miracle he survived as long as he did,” Miles said in a telephone interview.

Much of Miles’ knowledge of Burroughs and other Beat writers is first hand: The British writer knew him in the 1960s in London and lived at Allen Ginsberg’s commune in New York. Miles, a member of the underground himself and producer of music and poetic happenings, has also written biographies of Paul McCartney, Jack Kerouac, Ginsberg and others. (Miles allegedly introduced McCartney to hash brownies and owned a gallery where Yoko Ono met John Lennon.) Miles is also the author of “In the Sixties,” “In the Seventies” and “London Calling: A Countercultural History of London since 1945.”

But for information on Burroughs’ childhood in St. Louis, Miles draws from the research of Burroughs’ friend and business manager, James Grauerholz. Miles writes of Burroughs’ home:

“It was a large, comfortable five-bedroom house with a fifty-foot lawn in front sloping down to the street and a large garden behind with a fish pond surrounded by rocks. The backyards were separated by high wooden fences twined with roses and morning glory. At the bottom of each yard was an ash pit; the houses on the private roads were not connected to the main sewer, and from his bedroom window young Billy could sometimes see rats scurrying about.”

Billy was named for his grandfather, who developed the adding machine. His grandfather died at age 41, leaving stock to his children. Mortimer Burroughs sold his final shares in the company in 1929, just before the stock market crash, for the modern equivalent of more than $3.5 million.

As a child, Billy attended the Community School, John Burroughs School, and another expensive private school, Los Alamos Ranch School, in New Mexico. He earned his bachelor’s from Harvard University, where he majored in English and easily got A’s.

Although Burroughs the writer would rebel against his bourgeois upbringing, he was happy to receive money from his parents, Mortimer and Laura Lee Burroughs, until he was 50 years old. That allowance, about $200 a month, gave him much freedom and drug money.

Miles notes, “He had tremendous privileges and advantages over other people. No question about that.”

Throughout Burroughs’ books, memories of St. Louis would make appearances ― a talk with his father in the garden, a pet guinea pig, smells from the River Des Peres.

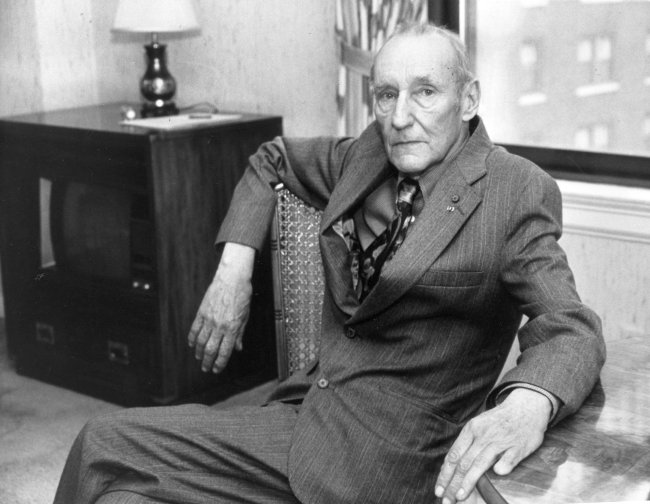

He also retained the impeccable manners he grew up with, Miles says. In London, Burroughs would wear three-piece suits and stand up when women entered the room.

Those manners didn’t soothe, however, the embarrassments that his parents suffered.

“Having a famous homosexual junkie in the family is not the best thing, really,” Miles says.

By the early ’60s, Burroughs’ parents had moved to Florida, escaping not just Midwestern winters but also, perhaps, hometown gossip and newspaper articles about their son.

Burroughs’ writings were nonlinear, often a collage of scenes or stories, and his life itself is often remembered for unusual, even tragic events:

― By the early 1940s, Burroughs had already had at least one stay in a mental institution (diagnosis: schizophrenia). His sexual obsession with a man had led him to cut off part of a finger. While living in New York, he would try heroin and quickly become addicted. In 1946, he was arrested for forging a doctor’s prescription. When his father bailed him out, Mortimer merely told his son, “It’s a terrible habit.” Although concerned, Burroughs’ parents maintained control of their emotions.

― Also in New York, he becomes close friends with the group that would become known as the Beat writers. Burroughs was arrested as a material witness after his friend Lucien Carr stabs another friend, David Kammerer, to death. His father returns to New York to bail him out.

― In 1946, Burroughs buys 40 hectares of land near Huntsville, Texas, and moves there with Joan Vollmer, who loved him and would become his common-law wife. She was addicted to amphetamines and alcohol, and their son, Billy, was born addicted to amphetamines in 1947. Billy would die at age 33, an alcoholic. Texas farming, even with paid cotton pickers, proves too difficult. In 1949, Burroughs is arrested for drug possession. His father bails him out and he goes to a sanitorium. He decides to skip the country and move the family to Mexico.

― In Mexico City, Bill, very drunk, tries to shoot a glass off Joan’s head. He hits her and she soon dies. Later he blames, in part, an “Ugly Spirit.” Burroughs’ son is sent to live with his grandparents.

― For the next two decades, Burroughs lives as an expatriate, looking for the drug yage in the Amazon, pursuing teenage boys in Tangier, then dressing as an Englishman in swinging London. His groundbreaking book “Naked Lunch” (published in Paris as “The Naked Lunch” in 1959) comes out in the United States in 1962. It’s banned in Boston as obscene, but after hearings that included testimony from Norman Mailer and Allen Ginsberg, Massachusetts’ top court accepts that it does have social value.

Later, Burroughs would work on what were called “cut-ups,” which started with piles of newspapers. A line of text would be cut out and the story underneath would show through, revealing a humorous sort of “reading between the lines.”

Miles writes that Burroughs’ writing methods were often unorthodox: “his correspondence with Allen Ginsberg produced his first four books. His experiments with cut-ups and textural juxtaposition using columns and scrapbooks led him far from writing into recording tape cut-ups; photographic collages, photo series, and pattern making ...”

As Burroughs’ biographer says, he was seen “as a great writer, a junkie, a murderer, a misogynist, a member of the original Beat Generation, a mentor to the youth movement of the sixties, a political philosopher, a psychic, a leading gay activist, an artist, a gun advocate, an actor, a humorist, and a ‘good ’ol boy.’”

Burroughs’ outlaw junkie reputation would influence writers, filmmakers and punk musicians. Today, readers are still at odds over whether “Naked Lunch” is junk or genius. Comments on Amazon.com range from “it is for those of us who seek the truth” to “glorified crap.”

Although Burroughs never cultivated a particular image, he could meld into a variety of backgrounds. Miles writes that “Burroughs carefully modified his image to fit his chosen role. He cultivated a mysterious, disconcerting aura.”

Buried near his grandfather, lot 3938 in St. Louis’ Bellefontaine Cemetery, Burroughs’ grave is one of the cemetery’s most visited.

By Jane Henderson

(St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

(MCT Information Services)

Over his life, Burroughs traveled much of the world and found myriad substances to induce more visions and dreams, which he recorded in books or used as inspiration for art of one kind or another.

This week is the 100th anniversary of Burroughs’ birth ― on Feb. 5, 1914 ― and his literary kingdom is international, a destination for both scholars and modern beatniks. Novels such as “Naked Lunch,” “Junky” and “Queer” retain an outlaw reputation more than 50 years after he wrote them. The Burroughs oeuvre ― obscene, amoral, transgressive ― enthralls dedicated members.

“His work still has the power to shock, which is pretty hard these days,” Miles says.

Miles’ 700-page biography shows how Burroughs’ life was mirrored in his writing while warning that some of Burroughs’ tales were likely exaggerated.

One thing that wasn’t exaggerated was Burroughs’ addictions, even though he lived until 83.

“Considering what he did to his body over the years, it’s a miracle he survived as long as he did,” Miles said in a telephone interview.

Much of Miles’ knowledge of Burroughs and other Beat writers is first hand: The British writer knew him in the 1960s in London and lived at Allen Ginsberg’s commune in New York. Miles, a member of the underground himself and producer of music and poetic happenings, has also written biographies of Paul McCartney, Jack Kerouac, Ginsberg and others. (Miles allegedly introduced McCartney to hash brownies and owned a gallery where Yoko Ono met John Lennon.) Miles is also the author of “In the Sixties,” “In the Seventies” and “London Calling: A Countercultural History of London since 1945.”

But for information on Burroughs’ childhood in St. Louis, Miles draws from the research of Burroughs’ friend and business manager, James Grauerholz. Miles writes of Burroughs’ home:

“It was a large, comfortable five-bedroom house with a fifty-foot lawn in front sloping down to the street and a large garden behind with a fish pond surrounded by rocks. The backyards were separated by high wooden fences twined with roses and morning glory. At the bottom of each yard was an ash pit; the houses on the private roads were not connected to the main sewer, and from his bedroom window young Billy could sometimes see rats scurrying about.”

Billy was named for his grandfather, who developed the adding machine. His grandfather died at age 41, leaving stock to his children. Mortimer Burroughs sold his final shares in the company in 1929, just before the stock market crash, for the modern equivalent of more than $3.5 million.

As a child, Billy attended the Community School, John Burroughs School, and another expensive private school, Los Alamos Ranch School, in New Mexico. He earned his bachelor’s from Harvard University, where he majored in English and easily got A’s.

Although Burroughs the writer would rebel against his bourgeois upbringing, he was happy to receive money from his parents, Mortimer and Laura Lee Burroughs, until he was 50 years old. That allowance, about $200 a month, gave him much freedom and drug money.

Miles notes, “He had tremendous privileges and advantages over other people. No question about that.”

Throughout Burroughs’ books, memories of St. Louis would make appearances ― a talk with his father in the garden, a pet guinea pig, smells from the River Des Peres.

He also retained the impeccable manners he grew up with, Miles says. In London, Burroughs would wear three-piece suits and stand up when women entered the room.

Those manners didn’t soothe, however, the embarrassments that his parents suffered.

“Having a famous homosexual junkie in the family is not the best thing, really,” Miles says.

By the early ’60s, Burroughs’ parents had moved to Florida, escaping not just Midwestern winters but also, perhaps, hometown gossip and newspaper articles about their son.

Burroughs’ writings were nonlinear, often a collage of scenes or stories, and his life itself is often remembered for unusual, even tragic events:

― By the early 1940s, Burroughs had already had at least one stay in a mental institution (diagnosis: schizophrenia). His sexual obsession with a man had led him to cut off part of a finger. While living in New York, he would try heroin and quickly become addicted. In 1946, he was arrested for forging a doctor’s prescription. When his father bailed him out, Mortimer merely told his son, “It’s a terrible habit.” Although concerned, Burroughs’ parents maintained control of their emotions.

― Also in New York, he becomes close friends with the group that would become known as the Beat writers. Burroughs was arrested as a material witness after his friend Lucien Carr stabs another friend, David Kammerer, to death. His father returns to New York to bail him out.

― In 1946, Burroughs buys 40 hectares of land near Huntsville, Texas, and moves there with Joan Vollmer, who loved him and would become his common-law wife. She was addicted to amphetamines and alcohol, and their son, Billy, was born addicted to amphetamines in 1947. Billy would die at age 33, an alcoholic. Texas farming, even with paid cotton pickers, proves too difficult. In 1949, Burroughs is arrested for drug possession. His father bails him out and he goes to a sanitorium. He decides to skip the country and move the family to Mexico.

― In Mexico City, Bill, very drunk, tries to shoot a glass off Joan’s head. He hits her and she soon dies. Later he blames, in part, an “Ugly Spirit.” Burroughs’ son is sent to live with his grandparents.

― For the next two decades, Burroughs lives as an expatriate, looking for the drug yage in the Amazon, pursuing teenage boys in Tangier, then dressing as an Englishman in swinging London. His groundbreaking book “Naked Lunch” (published in Paris as “The Naked Lunch” in 1959) comes out in the United States in 1962. It’s banned in Boston as obscene, but after hearings that included testimony from Norman Mailer and Allen Ginsberg, Massachusetts’ top court accepts that it does have social value.

Later, Burroughs would work on what were called “cut-ups,” which started with piles of newspapers. A line of text would be cut out and the story underneath would show through, revealing a humorous sort of “reading between the lines.”

Miles writes that Burroughs’ writing methods were often unorthodox: “his correspondence with Allen Ginsberg produced his first four books. His experiments with cut-ups and textural juxtaposition using columns and scrapbooks led him far from writing into recording tape cut-ups; photographic collages, photo series, and pattern making ...”

As Burroughs’ biographer says, he was seen “as a great writer, a junkie, a murderer, a misogynist, a member of the original Beat Generation, a mentor to the youth movement of the sixties, a political philosopher, a psychic, a leading gay activist, an artist, a gun advocate, an actor, a humorist, and a ‘good ’ol boy.’”

Burroughs’ outlaw junkie reputation would influence writers, filmmakers and punk musicians. Today, readers are still at odds over whether “Naked Lunch” is junk or genius. Comments on Amazon.com range from “it is for those of us who seek the truth” to “glorified crap.”

Although Burroughs never cultivated a particular image, he could meld into a variety of backgrounds. Miles writes that “Burroughs carefully modified his image to fit his chosen role. He cultivated a mysterious, disconcerting aura.”

Buried near his grandfather, lot 3938 in St. Louis’ Bellefontaine Cemetery, Burroughs’ grave is one of the cemetery’s most visited.

By Jane Henderson

(St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

(MCT Information Services)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids to return soon: report](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050713_0.jpg&u=)