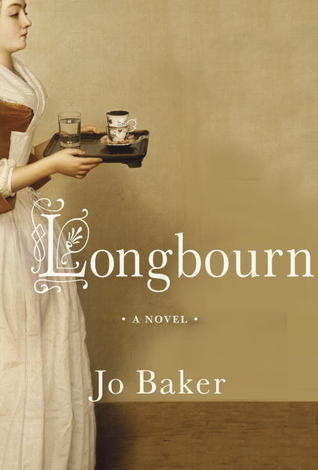

By Jo Baker

(Alfred A. Knopf)

Looking at the ever-growing list of contemporary fiction presuming to improve on Jane Austen (with or without zombies), readers may well wonder why they can’t leave the poor author alone. Happily, Jo Baker’s “Longbourn” is no mere riff but a fully imagined rejoinder to “Pride and Prejudice” that casts a sharp working-class eye on the aristocratic antics of Elizabeth Bennet, Mr. Darcy and their friends.

The Bennets’ housemaid Sarah is Baker’s heroine, and she seems far more heroic than the pampered family as we follow her through the never-ending rounds of backbreaking labor required to maintain a Georgian household. Muddy petticoats must be scrubbed clean with lye soap that leaves her hands cracked and bleeding; when inclement weather prevents young ladies from journeying to town for shoe-roses to ornament their dancing slippers, Sarah must trudge through the rain for them. “If they send you on a fool’s errand in foul weather again ... I’ll go instead,” says the new footman, James. Sarah has been suspicious of this young man, hired despite his shadowy background, and we learn that James has his reasons for keeping aloof from the spirited housemaid. But a tender love story grows from their undeniable attraction, made more poignant because servants are at the mercy of forces beyond their control.

We observe the Bennet girls’ romances at a distance, though the reprehensible Wickham behaves as unscrupulously here with the help as he does in Austen’s original with Lydia. Baker is not entirely unsympathetic to the upper-class characters; Mrs. Bennet, in particular, gets gentler treatment than Austen gave her. But the author doesn’t airbrush the callousness of the privileged. Elizabeth doesn’t seem quite so charming after she responds to Sarah’s heartbroken inquiry about James (who has fled under duress from Wickham), “Oh, Smith! You mean the footman! You called him Mr. Smith. ... I thought you meant someone of my acquaintance. I thought you meant a gentleman.”

Austen’s novels amply demonstrate her cognizance of high society’s less-than-genteel underpinnings, albeit within the confines of her breeding. I think she would have appreciated Baker’s bracing rewrite from the underdog’s point of view. And I know she would have loved the well-deserved happy ending.

Joanna Trollope offers a more straightforward take in her modern-day rendering of “Sense and Sensibility” (Harper, $25.99), the debut volume in a British series pairing contemporary novelists with Austen titles. The plot and characters are almost exactly the same, the major difference being that Elinor, the sister with sense, is more openly exasperated by all the blithering around her than Austen allowed her to be, and that the many foolish and/or selfish secondary characters are far more obnoxious than they were in 1811.

Fans of the original will relish Trollope’s sly twists. In her version, Belle Dashwood was never actually married to Henry, whose death leaves her in dire financial straits when Henry’s son is persuaded by his odious wife to renege on a promise of support for Belle and her daughters. Belle’s cousin, Sir John Middleton, with whom they take refuge in Devon, is now the manufacturer of upscale country clothing; the home he provides, Barton Cottage, is an ugly new construction with all the mod cons, and, as such, highly uncongenial to the romantic sensibility of middle daughter Marianne Dashwood. Marianne has asthma, which gives a lot more plausibility to both her chance rescue by Willoughby, the weak-willed Adonis who breaks her heart, and to her life-threatening illness at the novel’s climax.

It’s good, malicious fun that smarmy Robert Ferrars turns out to be gay―not that their mother, who unfairly favors him over Elinor’s true love, Edward, has a clue about it. That makes it so much more ridiculous when nasty little Lucy Steele jilts Edward, who has nobly maintained an unwise youthful engagement to her, so that she can marry Robert.

Elinor remains the calm, lovable center of this storm of silliness, updated only in the architecture degree derailed by her family’s financial crisis. Edward, alas, is as colorless as before, and Trollope’s Colonel Brandon is so charming we wish even more than usual that he and Elinor would get together. But Trollope honors her predecessor’s intentions and reserves him for Marianne, whose chastened renunciation of excess sensibility is movingly portrayed in this faithful retelling. (MCT)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[Pressure points] Leggings in public: Fashion statement or social faux pas?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050669_0.jpg&u=)