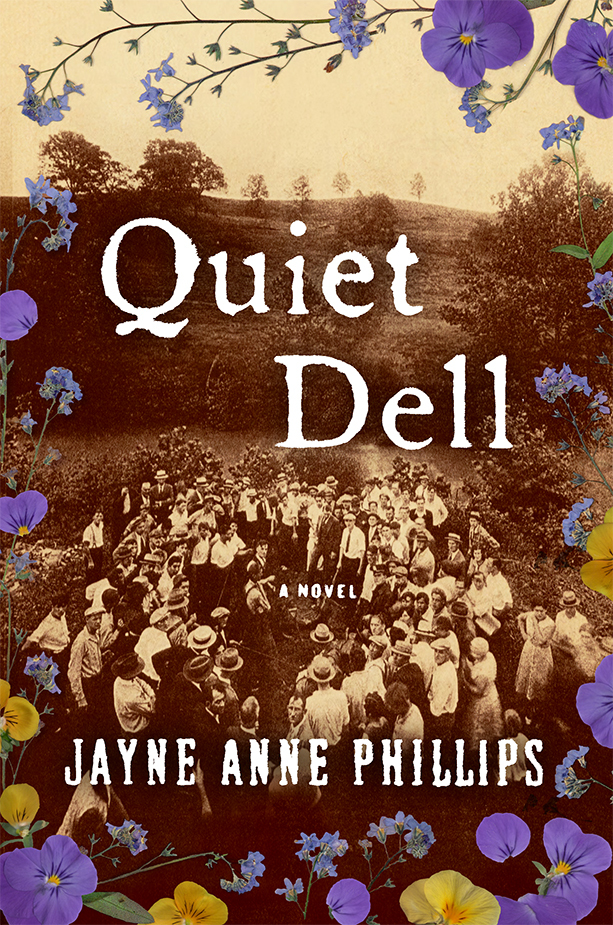

Jayne Anne Phillips revisits a murder in ‘Quiet Dell’

By Claire LeePublished : Oct. 17, 2013 - 19:10

By Jayne Anne Phillips

(Scribner)

Jayne Anne Phillips grew up in West Virginia hearing about the infamous Quiet Dell murders of 1931, real-life killings of a widow and her three children at the hands of a con man she met through a lonely hearts club.

Phillips learned about the grisly case from an unlikely source: her mother, who remembered as a child walking past the “murder garage” where Asta Eicher and her children ― 14, 12 and 9 ― died, the road nearby lined with cars of souvenir-seekers.

The image clearly seized Phillips’ imagination. Now an English professor and author, she spent years quietly researching and writing her “hidden book,” emerging with a story on one of the first nationally sensationalized crimes that is built on historical fact but overlaid with a warm, fictional narrative.

Phillips’ extensive reporting ― she quotes from newspaper stories, letters between Eicher and her “suitor” and the trial transcript ― gives the book its considerable heft. And her creation of a Chicago reporter named Emily Thornhill helps to frame the story of the eight-decade-old event in a fresh way. “Quiet Dell” is a smart combination of true crime, history and fiction tied together with Phillips’ seamlessly elegant writing.

Though the first 100-plus pages of the book are devoted to describing the soon-to-be-slain family, the lengthy windup pays off once Emily comes on the scene. She’s a 35-year-old career woman at a time when that was still something of a rarity. Her version of events provides the compassionate lens through which we learn the grim details of the investigation and arrest of Harry Powers, whose trial was held in an opera house large enough to accommodate the crowd of spectators. There’s an attempt by a lynch mob ― Phillips supplies a black-and-white photo as proof ― and another photo of the family dog named Duty who was the sole survivor.

In addition to the bodies of Eicher and her children, another woman he had wooed through the matrimonial society was also discovered, dead and buried near Powers’ garage. The building had been specially fitted out with soundproofed cells.

After Powers’ arrest, police found scores of letters from other women he was courting through the mail, leading to speculation that “the Bluebeard of Quiet Dell,” as he was nicknamed, had killed many others. The public was mesmerized.

“Quiet Dell No Longer Quiet,” reads one excerpt from an August 1931 article in The Clarksburg Telegram. “No accurate estimate can be made of the numbers who have visited the ‘Murder farm.’ State policemen say they were too busy handling traffic to attempt to count the automobiles but there must have been 50,000 at least, yesterday and Saturday night.”

As the book proceeds to its dark conclusion, Emily offers readers a glimpse of light. Her relationship with a banker who plays a role in the case and her tendency to adopt the people and creatures she comes across in her reporting create a sense of hope despite the harrowing crime.

Phillips’ writes with a tone that is sometimes impressionistic, sometimes hard-edged. It’s a linguistic balancing act that results in an emotional chiaroscuro. Sometimes, she says, darkness overcomes the light. (MCT)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Pressure points] Leggings in public: Fashion statement or social faux pas?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050669_0.jpg&u=)